As an SFU student since 2009 and Bachelor of Science student in the faculty of Health Sciences since 2012, it is strange that SFU was the last place that I searched for a co-op position. When searching for prospective research positions, I would pursue positions I found at UBC, the BC Cancer Agency and similar organizations posted on MyExperience. It was only at the insistence and advice of my co-op advisor to seek research positions at SFU that I came across the Epigenetics Lab, led by Gratien Prefontaine. I had known Dr. Prefontaine through a class I had taken a few years prior and was intrigued by epigenetics. When I first arrived at the lab, I was as nervous as I have ever been, as I had never been in a research environment before and was skeptical that my skills would translate into any initial success.

The first lesson I learned was not on a specific technique or a test of my pipetting skills, but rather that the most important asset you have to offer is time. The typical 9-5 work schedule does not fully apply to work in a research lab because tissue cells may need splitting over weekends, techniques may run over time, and reagents that are needed for a protocol may run out and need to be ordered (and therefore waited upon). One of the strengths I found being a co-op student is that, unlike students who volunteer while taking classes, my whole focus was centered on my work in the lab. If Dr. Prefontaine needed me to head a project or perform daily duties, I was available and not distracted by other studies. I was able to fully immerse myself in the work and not have to worry about upcoming exams or school projects.

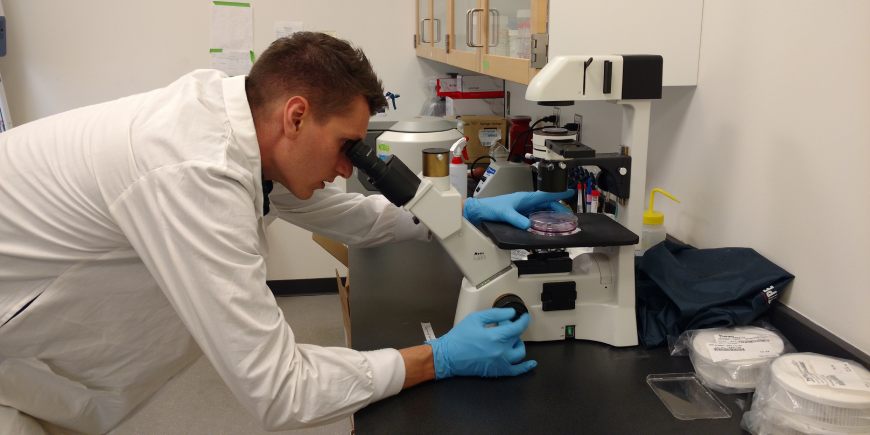

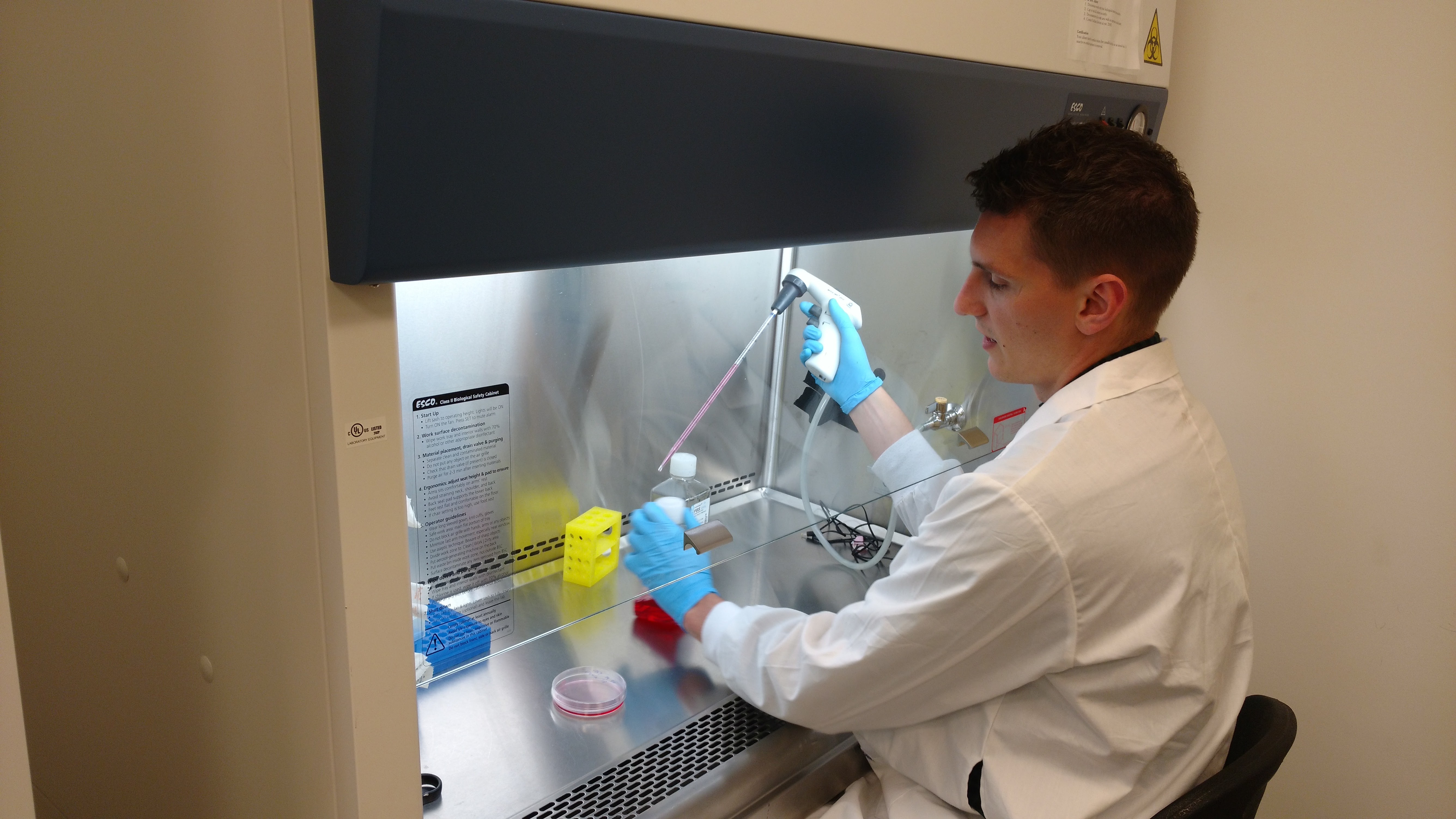

A typical day in the lab would generally start with the maintenance of tissue cells. One of my tasks was to keep a specific cell line (SY5Y) happy along with an identical cell line that had a specific protein knocked out. Different assays could then be used to test how the knockout of the specific protein affected cell signaling and how different receptors would be up regulated or down regulated. In order to perform these assays, there had to be enough plates of confluent cells (plates where cells were grown to a large proportion) for both cell lines. This meant having to plan out a week in advance when to split cells, at what dilution to split them at, and switching the media so that they grew at an expected rate. It also required absolutely sterile conditions as cross-contamination between cell lines could delay experiments a few weeks. I would periodically test the conditions of the knockout cell line to confirm that the protein of interest was absent through Western Blots.

Besides cell maintenance, I took on any assignment that would greatly help out the graduate student in my lab and make life easier for Dr. Prefontaine. This included techniques and assays such as Western Blots, Immunoprecipitation, CHIP, PCR, and many others. Almost every technique I performed for the first time never had the desired results, whether it was a DNA concentration that was very low or a Western blot that showed no bands during imaging. One of the early I lessons I learned in the lab was to never sink into a frustration with unexpected results. Instead, figure out why results did not work out, come up with a possible solution, and try again. Many times, it was as simple as adding an incorrect buffer or forgetting one step out of twenty in a protocol.

Along with tissue cells, I learned how to work with bacterial cells, specifically DH5 alpha E. coli cells. Our lab always had to have a stock of competent cells, and this was one of the earliest challenges that I was assigned to produce. After a couple of utter failures, I was able to successfully produce competent cells that we could use for future cloning experiments. Plasmids would be transformed into these cells and digested with restriction enzymes before ligating sgRNA’s into the plasmid. Using different combinations of restriction enzymes provided us information on whether positive or negative clones emerged and whether we needed to sequence these oligonucleotides.

When I re-cap my eight months spent in the lab, there are so many aspects about the position that I truly appreciate. There is the autonomy over your own schedule that allows you to plan out your days in advance based on the techniques you need to use and the results that follow. There are the challenges that each project and task offers where you have to figure out how to make your next experiment go smoother and yield better outcomes. This brings excitement to your work as every day you are improving your skills and knowledge about the cells you work with or about the plasmid that you are transforming. Most of all, you surround yourself with an ambitious but humble group of undergraduate and graduate students who are always available to offer support and assistance. This avenue of support will only be advantageous if you actually communicate with those you work with. My biggest weakness coming into the lab and one that I am still working on is communication. I have always preferred an independent work atmosphere but believe it or not, I do not know more about epigenetics than the PhD student who has been in the lab for a few years or Dr. Prefontaine himself. They are an amazing reservoir of experience that I could have taken greater advantage of and it’s a lesson that I will take with me.

Overall, I would highly recommend any student who is looking to gain experience in a research lab to pursue this through SFU co-op as it offers you the time and focus that no other program can. The connections you make and the effort that you put in will greatly reward you in any future endeavors and may shape your career for years to come.

Beyond the Blog

-

For more about opportunities like Phillip's, visit the Health Sciences Co-op homepage.