In this interactive, experiential workshop we explored the history and impacts of colonization in Canada, with the aim of understanding how we can work to create positive social change. We focused primarily on specific contexts for non-Indigenous people's decolonizing work. This included creating space to define who we are as individuals and look at what decolonization means, within ourselves and the systems we work within. We practiced taking personal responsibility, including looking at what stops us and how we can overcome these struggles. Our aim is to build allegiance with centuries of Indigenous resistance and to build new models for moving forward.

The workshop was facilitated by Rain Daniels. Rain is Anishinaabe from the Saugeen Nation in Ontario, born in Coast Salish territory in Vancouver. She has worked with both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and communities for the last 20 years in capacities that include front-line work and community development. She also facilitates training, educational workshops, and community processes. Enhancing working relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people is the focus of her work.

The Simon Fraser Public Interest Research Group (SFPIRG) is a student-funded and student-directed resource centre dedicated to social and environmental justice. SFPIRG is founded on a set of values that have been developed by successive generations of students who care about social and environmental justice. These values include a commitment to the work of ending all forms of oppression; and one key piece of anti-oppression is the work of learning about and resisting colonialism - or, to put it another way, the work of promoting decolonization.

At SFPIRG we see decolonization as a process that is relevant to every one of us. As Nora Burke wrote in Building a “Canadian” Decolonization Movement: Fighting the Occupation at “Home,” “Decolonization is not a process which entails solely the Indigenous nations of this continent. All people living in Canada have been distorted by colonialism.” To recover from this distortion requires that each of us learn new ways of relating to one another, to the land, to Indigenous nations and to the Canadian state.

At SFPIRG we try to ground this decolonization work in truth telling.

For those of us who are members of settler society,* this is not something that comes easily. (See the end of this article for definitions and discussion of terms with an * next to them.) Settlers on this land have generally been raised with little understanding of Canada’s history as a settler colonial state, and even less understanding of what the ongoing reality of colonialism actually means in the lives of Indigenous people today. Few of us can name the Indigenous nations who have been displaced from the land on which we live, study and work. Likewise, most of us have little or no understanding of how each of us, as individuals and as members of settler communities, are implicated in an ongoing process of colonialism that continues to do immense harm and injustice to Indigenous communities. It is important to realize that ‘implicated’ does not mean ‘evil’ or ‘to blame;’ but, at least for those of us who want to see ourselves as supporters of social justice, it does mean an obligation to learn about and take action in support of decolonization.

Colonialism spins a story about itself that obscures the truth. We hear about ‘hard working settlers transforming empty land,’ and how residential schools are ‘ancient history.’ We don’t hear about how the North West Mounted Police (which became the RCMP) was created specifically to remove Indigenous people from their lands in order to make way for European settlers, or the fact that the last residential school in Canada closed in 1996. We also don’t learn that during significant periods of the residential school era, there were mortality rates among Indigenous children of 30 - 60%. We don’t hear that, at this very moment, the number of Indigenous children who are in Canada’s terribly underfunded & under-monitored foster care system outnumber all the children who were ever in residential schools. We hear about ‘special rights’ for Indigenous fisheries and the myth that Indigenous folks don’t pay taxes. But we never hear about the countless ways in which the Canadian state has broken and continues to disregard treaties, British colonial law, current Canadian law and International law. We don’t hear about how, in a relentless pursuit of wealth and ‘development’, Canada and its provinces continue to violate Indigenous title to land in a process that leaves Indigenous communities with limited or no economic base, with people forced to live in dire poverty.

Colonialism lies to us all in countless ways; in such a context, truth-telling is both powerful and necessary.

Here are some things that we at SFPIRG believe to be true:

-

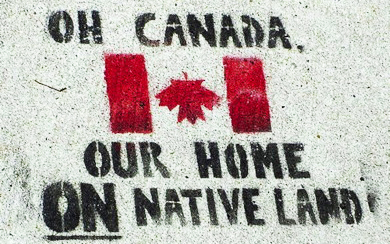

We acknowledge that SFPIRG is located on unceded* Indigenous land belonging to the Coast Salish* peoples.

-

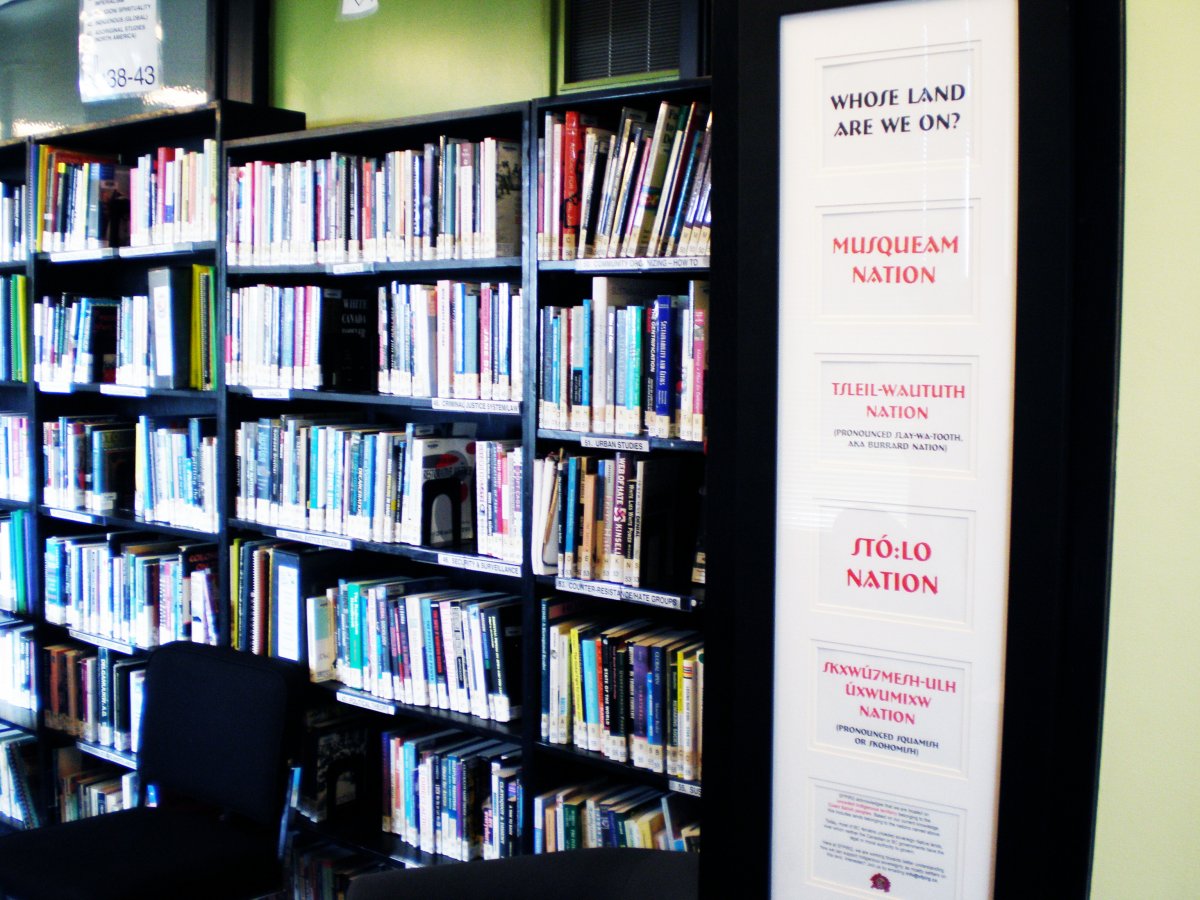

The Coast Salish nations are many, and their territories cover a large section of what is now called British Columbia. Based on our current knowledge, SFU campuses occupy land that belongs to four of the Coast Salish nations - the Musqueam, Skxwú7mesh-ulh Úxwumixw (pronounced Squamish or Skohomish), Stó:lo & Tsleil-Waututh (pronounced: slay-wa-tooth, aka Burrard) nations.

-

SFPIRG, as a student organization tied to a university, arises from and is a part of the settler colonial state and thus exists at the expense of the Indigenous people who have both moral and legal right* to this land and to self governance.

-

As an organization we therefore have an obligation to (and we want to!) better understand how we can promote the work of decolonization.

As a starting point, we are working on this by trying to enact truth-telling in all the different areas of our work. This includes things like having permanent framed acknowledgements of Indigenous territories in the SFPIRG lounge and meeting room; and including a territory acknowledgment in all our outreach materials (like our website, email newsletters and printed materials). On our website there is a downloadable map of Coast Salish territories for visitors to learn more about, as well as links to the websites of the Musqueam, Squamish, Sto:lo and Tsleil-Waututh nations. We are planning to take another step in this regard by developing a booklet that will be distributed on all SFU campuses that will inform members of the SFU community about the nations who hold title to this land and the ongoing work that each of those nations are doing to secure a better future for their communities. All members of the campus community who might be interested in working on this project are more than welcome to come and talk with us.

It is also our intention and practice that every SFPIRG meeting and event starts with a sincere acknowledgement of Indigenous territory. We strive to learn and use the names of specific Coast Salish nations to highlight the fact that these are sovereign nations, each with their own relationship to the land.

We want to improve our capacity to discuss decolonization in a way that can encourage other members of settler society to engage with this reality, and to seek out further learning. As part of this effort, we have a growing Indigenous section in our Social Justice Lending Library and we are continually seeking new resources. We also invite speakers and facilitators to present talks and workshops about decolonization and related topics as part of our programming. Last year, for example, Jessica Danforth (then Jessica Yee) accepted our invitation to speak about the connections between decolonization and sex worker rights. Earlier this summer we had a talk called “Decolonization & the Mind” presented by Dr Michael Yellowbird - a writer and social worker from the Arikara (Sahnish) and Hidatsa Nations in North Dakota who is greatly sought after for his knowledge on a range of topics such as health, Mind Body Medicine (MBM), mindfulness, neuroscience, social work, and nutrition.

These are just some of the ways we try and engage in a process of decolonization. We welcome anyone - students, professors, campus groups - who would like to have conversations about what decolonization might look like to come and talk with us, not because we are experts, but because we are on the same learning journey and we need as many people as possible to join in the work.

We are based in TC326 in the Rotunda on SFU’s Burnaby Campus. For more information about our work, please visit www.sfpirg.ca.

Definition of Terms:

*Settler societies are societies founded upon the displacement or elimination of Indigenous peoples. Settler societies are the product of settler colonialism, a form of colonialism that differs somewhat from other forms of colonialism. Whereas settler colonialism is characterized by invasion and displacement of local populations in order to make way for settler populations, other forms of colonialism emphasize resource and labour extraction. These forms of colonialism are not mutually exclusive. The vast majority of settler societies began with European imperialism and remain dominated by people of European decent (white folks).

One does not have to be white to be a member of settler society. As is noted by the group Unsettling Minnesota in their Points of Unity:

-

All people not indigenous to North America who are living on this continent are settlers on stolen land.

-

All settlers do not benefit equally from the settler-colonial state, nor did all settlers emigrate here of their own free will.

That last bit means that not all settlers have the same relationship to colonialism. The Unsettling Minnesota group also notes that “...slavery, hetero-patriarchy, white supremacy, market imperialism, and capitalist class structures …[are] among the primary tools of colonization. These tools divide communities and determine peoples’ relative access to power.”

One article that explores this complex reality is Moving Beyond a Politics of Solidarity Towards a Practice of Decolonization by Harsha Walia, a Vancouver based activist.

* Unceded territory refers to land in North America that was never ceded to a government entity by Indigenous peoples, and that has never been set apart, legislated, founded, created or established as a reserve. Today, most of BC remains unceded sovereign Native lands, over which neither the Canadian nor the BC government has the legal or moral authority to govern.

* Coast Salish The “First Nations - Land Rights and Environmentalism in British Columbia” website says of the Coast Salish peoples: “Coast Salish peoples inhabit the Northwest Coast of North America, from the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon, north to Bute Inlet in British Columbia. Coast Salish territories includes much of the ecologically diverse Georgia Basin and Puget Sound known as the Salish Sea ... This huge drainage basin comprises the coastal mainland and Vancouver Island from Campbell River and Georgia Strait south through the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the Lower Fraser Valley and the lowlands of Puget Sound.” Click the link above to learn more.

* Legal right By our understanding colonialism is illegal, whichever legal system one uses. Certainly under Indigenous legal systems the settler occupation of Indigenous land is illegal. This might seem like an odd and obvious thing to write, but it is important to start here: Indigenous peoples, including the Coast Salish nations on whose land we live, work and study, have their own valid legal systems with laws related to land. Canadian colonialism violates those laws. The occupation of unceded territories also violates British colonial law which required treaties. British colonial law also required that treaties be honoured. Setting aside for the moment the issue of treaties made under duress, it is a fact that Canada has repeatedly violated the treaties that were made with Indigenous peoples. Settler colonialism is also illegal under international law which prohibits the displacement of peoples from their land and the transfer of non-Indigenous populations onto occupied land. Even the Canadian state’s own legal system has, in a way, recognized the illegality of the settler colonial process. In the Supreme Court of Canada's legal decision Delgamuukw vs British Columbia the Court ruled that Indigenous title to land exists (in other words, ownership of unceded Indigenous territories remains with Indigenous people) and that this title encompasses the right to exclusive use and occupation of the land. Of course, the Supreme Court of Canada remains a colonial entity and it wasn’t about to rule the Canadian state, and thus itself, into complete illegitimacy, so it also held that (somehow) the Canadian state had a right to infringe on Indigenous title, but that this would require a compelling reason and that the Canadian state behave in accordance with its ‘fiduciary duty’ - a highly problematic concept, but one which requires consultation with Indigenous peoples before infringing on Indigenous title. Finally the Court also ruled that if there is infringement of Indigenous title, there must be economic compensation. The fact that provinces like BC continue to infringe on ever more Indigenous territory without land claim agreements, consultation or compensation means that these provinces are acting in violation of Canadian law.