Greetings,

I want to first begin by providing some context and background info about this paper. Currently, I am a third year university student, working toward obtaining a degree in Sociology.

Quite recently, in one of my sociology classes we were given the opportunity to choose any topic of our interest that is relevant to sociology, and to write about it. I knew right away that I was going to choose this topic, because I felt an urgency and responsibility to contribute to the voices of dissent which challenge(s) the notions that this is not a sociological phenomenon, which it indeed most certainly is.

Moreover, I did not choose this topic merely for the fact that I am an Indigenous person. Nor did I necessarily choose it solely because of its intrinsic and fundamental link(s), not to mention relevancy, to sociology. I chose this topic because it is an absolutely plaguing social problem faced not only by the Indigenous community, but all of Canadian society, and therefore deserves much more attention.

Once the paper was completed and handed in, I began thinking that what I wrote needs to be shared. And so I began by first sharing it with a couple of friends and relatives, with whom I read aloud and/or emailed it to. Though I still felt that my words needed more widespread attention of others.

To which I then decided to share it publicly on Facebook, where I encouraged family and friends to also share it and expand its circulation for others to see as well. The reception was successful enough that I was approached by an individual who offered to publish it on this platform, which I thought to be a fantastic idea.

In addition to sharing the entire text of this paper, I have also decided to share it via voice-recording for a couple of reasons. First, it is because there are many people whom I know that enjoy hearing me speak and appreciate my voice. Second, I believe that by actually hearing the author read their work, one can truly gather where the emphasis exists. Thirdly, it is tradition within Indigenous cultures to pass down stories and information via one’s voice, hence the phrase “oral tradition”. Therefore, if you wish, you can find my voice recordings of this paper in TWO parts here: (1) http://chirb.it/k9ca6K & (2) http://chirb.it/zxP5IC

(Just know that this paper is eight pages in length, and I had no intention to read it through as quickly as possible, so the total length of these recordings is about 32 minutes.)

My goal with this paper is to raise consciousness, and have an open, honest, and fact based interrogation on this topic. I also hope that you the reader carry-on the conversation that I highlight in this paper, for the sake of the dignity, humanity, and respect of the victims of this phenomenon. Every difference does count.

In this paper I examine an issue that has existed since the inception of what is now called Canada. This issue is a sociological phenomenon that has historically been grossly undermined, denied, ignored, accepted, and for a long time, even encouraged by both the Canadian state, and the majority of its white settler populace. The issue I speak of is (and has been) the systematic devaluing and marginalization of Indigenous women in Canadian society. The basis of this paper is to try to better understand, as well as bring more awareness, to a very grim & shameful aspect of Canadian society, which is the jarring amount of murdered & missing Indigenous women & girls that has proliferated before us. This is a topic which not only deserves more widespread attention, but demands it, because it is disgraceful for a country like Canada to continue to collectively ignore, and/or remain silent about the fact that there exists nearly 1,200[1] documented cases of either murdered or missing Indigenous women, many of which are largely unsolved. This is the epitome of injustice for any society, especially one like Canada in this day and age. It is completely outrageous forany modern industrialized country to standby idly and allow for any of its citizens to experience this magnitude of violence. Thus, to understand this subject and all of its complexities, my goal with this paper is to examine the root causes that have fostered this phenomenon, as well as the circumstances which have formulated the contextual social realities for Indigenous women in Canada. To help guide my research, I have devised two complementary research questions: 1, How and why are Indigenous women devalued by (and/or within) Canadian society? And 2, how has this shaped the murdered & missing Indigenous women phenomenon?

Furthermore, to restate and reinforce the significance of this subject matter to the sociological discipline, as explained [per the guidelines] in Assignment 1, this topic is both highly relevant and important to sociology because it is a critical examination of many of the foundational beliefs, values, and influences that have all shaped Canadian society. Moreover, in terms of research methodology, [out of the two permitted choices] I use the literature review instead of content analysis, because for this particular topic it is the most convenient, and it offers the greatest potential of more in-depth content from scholarly sources, giving plenty of supporting information and broader analyses. In other words, with the help of existing analyzed materials, I, as a researcher have determined that with this methodology for this topic, can assemble more conclusive findings & formulate a stronger case by building on the evidence of other sources on this topic.

To help conceptualize my findings and work toward a thorough answer to my research question, I divide this paper into four brief sections. Where first, I will explain some of Canada’s history of European imperialism and white settler colonization. It is crucial to recognize and acknowledge this historical context because it provides for a better understanding of the social realities, experiences, and relationships between the differing demographics of contemporary Canadian society. Secondly, to complement this historical context, I will provide some statistics regarding the extent to which Indigenous women in Canada experience violence, to compare and contrast with that of the rest of Canadian society. I provide this data in order to supplement and combine it with the historical colonial context that has consequently resulted in deeply structural impediments which inherently, and disproportionately adversely impact Indigenous peoples, especially Indigenous women. Thirdly, I will integrate the voices and insights from an array of organizations, advocacy groups, and other social agencies, whose inputs will reinforce and support my findings, as well as echo my argument that this phenomenon requires much more attention and empathy from all of Canadian society. Lastly, I will end by sharing some of the very enlightening initiatives, commitments, and resources that have all been developing, allocated, and are dedicated to ending violence against Indigenous women, and reconciling at last, each and every case of a murdered or missing Indigenous woman.

On July 1, 1867, the country of Canada became a self-governing dominion of the United Kingdom of Great Britain. This move granted greater independence to four British colonies that had established themselves over the preceding years in Eastern Canada. This was indeed a pinnacle moment in history, as it began a new era for North America and the world. It also began what can best be described as a white settler society, which is, as Razack (2002) explains, a society established by Europeans on non-European soil[2]. Key to the foundations of such a society, lies an innate desirability to maintain exactly that, a white society. Therefore, at its base, Canada is a white settler society that is structured by racial hierarchy, where Europeans have proclaimed their dominance and have entrenched their entitlement over Canada by codifying it in law(s) and policy[3]. Thus, Canada’s origins lie on the dispossession and expropriation of Indigenous peoples by European conquerors[4]. In asserting their dominance, it is crucial for such societies to therefore create national mythologies where it is white people who came first upon these lands, while assuming that any and all Indigenous populations to be dead and/or assimilated[5]. “A quintessential feature of white settler mythologies is, [thusly], the disavowal of conquest, genocide, slavery, and the exploitation of the labour of people of colour[6]”. Consequently, European settlers have thus positioned and established themselves as “the group that is most entitled to the fruits of citizenship[7]”.

Corresponding with these fundamentally racist modes of supremacy and oppression, there also exists, within the Eurocentric mentality, additional beliefs, values, and notions which both extends and intersects the margins of domination & subordination over other social groups within Canadian society. In conjunction with the highly repressive social dynamics of colonialism and racialization, there are other social dynamics which proliferates the breadth of our social hierarchies and social stratification. There are dynamics such as classism, sexism, anthropocentrism, heterosexism, ableism, & paternalism, to name a few. Which in short, surmounts to a society that is structured to be dominated and maintained by white, able-bodied, heterosexual men. Therefore, this demographic is undoubtedly the most valued & privileged one within Canadian society, who control most, if not all of the economic, political, and ideological spheres of our society – this is called patriarchy. Though to best capture & take into account all of these interlocking and all-encompassing modes of oppression and discrimination, the term most applicable is intersectionality. Moreover, for the purposes of this paper, I am going to focus primarily on the intersectionality of colonialism, racialization and gender, and how these socially stratifying factors have worked to systematically marginalize and devalue women in Canada, especially Indigenous women and women of colour.

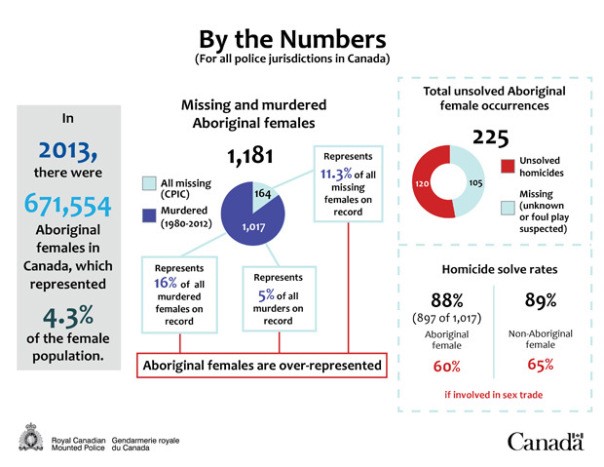

Crime and violence are prevalent social issues that exists in every human society, in one way or another. Though fortunately for Canada, the trends in crime rates for virtually all crimes have been steadily decreasing over the years. For example, homicide is at a 50-year low, attempted murder is at a 40-year low[8], and overall, police-reported crime rates have been steadily decreasing for over 20 years[9]. By all accounts, this is no doubt a generally positive prospect for Canadian society as a whole. Though hidden below the surface of these overall trends, there exists a very stark and different reality for Indigenous peoples, because despite accounting for only 4.3%[10] of the Canadian population, Indigenous peoples defy these statistical trends, and continue to be victims of high(er) levels of violence and crime. For instance, according to the 2009 General Social Survey on Aboriginal Violent Victimization, 12% of Indigenous people had reported they were victims of a violent crime, which is more than double to that of non-Indigenous people (5%). Of these incidents, physical assaults were the most common, followed by sexual assault. Indigenous people were also more likely to report being victimized multiple times. Furthermore, upon considering all socio-demographic factors as well as lifestyle characteristics, this survey concluded that the risk of crime victimization for Indigenous people compared to that of non-Indigenous was much higher, by approximately 58%[11].

These statistics demonstrate a sharp and undeniable disproportionality in regards to the likelihood and prevalence for which Indigenous people and non-Indigenous people experience violence and crime in Canadian society. However, it is Indigenous women in particular who bear the brunt and experience the mostviolence and crime. For instance, the rate of self-reported violent victimization for Indigenous women was about three times higher than that of non-Indigenous women[12]; and of these incidents, Indigenous women had a higher prevalence of reporting being injured than that of non-Indigenous women, by about 18%[13]. Moreover, despite the fact that the population of Indigenous women is only 4.3% of the overall female population, they make up about 11.3% of the total number of missing females in Canada today[14]. This disproportionate trend is also very similar when it comes to the most serious and lethal form of violence, homicide. According to the RCMP, between 1980 and 2012, the total number of homicide victims for Indigenous women equals approximately 16% of all female homicides in that period. Violence against Indigenous women can and does come in many forms, and it is abundantly, and clearly evident that within these statistics, Indigenous women are far too often overrepresented as victims of violence and crime in Canada. Which thusly indicates that deeply engrained in Canadian society, there lies inherent notions and values that have cultivated a social context which structurally operates, and is statistically proven, to systematically marginalize and in effect, devalue Indigenous women and girls.

To further expand on this historical context and these statistical findings, as well as emphasize the scope of this social problem, I am now going to incorporate the insights and conclusions of various other publications, organizations and societal agencies on this matter. Beginning with the United Nations’ Commission on the Status of Women (2013), which concludes that:

[V]iolence against women and girls is rooted in historical and structural inequality in power relations between women and men, and persists in every country in the world as a pervasive violation of the enjoyment of human rights. Gender-based violence is a form of discrimination that seriously violates and impairs or nullifies the enjoyment by women and girls of all human rights and fundamental freedoms. Violence against women and girls is… intrinsically linked with gender stereotypes that underlie and perpetuate such violence, as well as other factors that can increase women’s and girls’ vulnerability to such violence (pp. 8).

The Commission [also] reaffirms that indigenous women often suffer multiple forms of discrimination and poverty which [therefore] increase their vulnerability to all forms of violence; and [thusly] stresses the need to seriously address violence against indigenous women and girls (pp. 10).

The Native Women’s Association of Canada states similarly that Indigenous women “face life-threatening, gender-based violence, and disproportionately experience violent crimes because of hatred and racism[15]”. Thus, in order to break this cycle of violence, broader context and understanding(s) on this matter is necessary in order to fully grasp the severity of the issue. For this reason, Amnesty International (2008) examined this issue as well, and concluded that factors such as economic and social ostracism, in combination with prejudicial governmental policies, have worked to disproportionately impact Indigenous women, thus pushing them into more dangerous situations, and further into the margins of society[16]. In addition to this, some scholars also assert that the multifaceted systems of oppression (colonialism, patriarchy, racism) experienced by Indigenous women, is actually escalated and intensified by the further expansion of economic globalization and capitalism, because they both represent an attack and affront to the very foundations of Indigenous existence[17].

Though moreover, if we, as a collective aspire to truly and effectively pursue an anti-violent movement to end this violence against Indigenous women, then it is absolutely imperative to account for and acknowledge the reality of colonization and its intergenerational legacy upon Canadian society[18]. Also key to this recognition, is understanding that colonization is not simply a strategy or concept of the past, but rather, is an ongoing and presently existing narration that has perpetuated systemic violence, racism and discrimination against Indigenous peoples. Ultimately, colonization was (at least partially, if not solely) designed to intentionally deny culture, language and tradition(s) of Indigenous peoples, in an effort to impede and destroy identity. However, “It is also this understanding of the contemporary realities of colonization that informs… [proper] recommendations for change.[19]” Therefore, given this reality and accompanying social dynamics, in order to decolonize and end this violence against Indigenous women, it is crucial that the silence surrounding this violence must stop in order to re-humanize and (re)inject collective social value within Indigenous women.

Lastly, I briefly want to acknowledge some present day societal initiatives & developments that are dedicated to raising awareness and ending this systemic violence, to instead foster justice for Indigenous women, as well as the greater Indigenous community. In recent years, there have been some fairly prominent organizations that have called for specific measures and greater action(s) to be taken on this issue. For example, one of the many tenets of the Truth & Reconciliation’s 2015 Calls to Action reads:

We call upon the federal government, in consultation with Aboriginal organizations, to appoint a public inquiry into the causes of, and remedies for, the disproportionate victimization of Aboriginal women and girls. The inquiry’s mandate would include:

i. Investigation into missing and murdered Aboriginal women and girls.

ii. Links to the intergenerational legacy of residential schools (pp.8)[20].

Quite similarly, some of the core rights outlined in the United Nations’ 2008 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples reads:

Article 21

2. States shall take effective measures and, where appropriate, special measures to ensure continuing improvement of [Indigenous peoples’] economic and social conditions. Particular attention shall be paid to the rights and special needs of indigenous elders, women, youth, children and persons with disabilities.

…

Article 22

2. States shall [also] take measures, in conjunction with indigenous peoples, to ensure that indigenous women and children enjoy the full protection and guarantees against all forms of violence and discrimination (pp. 9)[21].

Furthermore, there have been many publications and/or organizations that have even outlined entire frameworks and potential national action plans aimed at reversing this violent trend within our society. One such organization is the Assembly of First Nations, who calls for comprehensive and coordinated action to both address and prevent further violence against Indigenous women and girls[22]. Human Rights Watch also recognizes this plaguing social issue, and one of their analyses entails a critical overview of the failures by law enforcement and the Canadian state to properly act on this problem and protect the victims[23]. The Walking With Our Sisters initiative is also a very notable advocacy group, whose sole dedication is to travel around North America, and raise more awareness on this pressing issue. Their methodology is also quite unique too, as they describe themselves as a “commemorative art installation for the missing and murdered Indigenous women of Canada and the United States”[24].

As for governmental initiatives and developments on this matter, after long resistance and denial of any injustice by all levels of government, 2015 has seen a huge shift in the just direction. For the last number of years there have been mounting voices that have been calling on the Federal Government of Canada to conduct a National Public Inquiry on murdered and missing Indigenous women. Though unfortunately these calls went unanswered, were ignored, undermined, and ultimately under-valued by the federal government, who, for (what seemed to be) the longest time, claimed that a national inquiry was not necessary because apparently enough resource allocation and prior studies on the matter was sufficient enough, at least in their eyes. Fortunately, however, this attitude and tone has undergone a radical change, thanks to the election of a new federal government on October 19, 2015. In this election I was very happy to see this notorious phenomenon become a central election issue, where all but one party had agreed that a national public inquiry was necessary. The new federal government is at last finally (more) in line with the rest of the country on this issue, alongside countless families, Indigenous governments and organizations, provinces, and territories who have all surmounted a united support for a national public inquiry on murdered and missing Indigenous women.

How and why are Indigenous women devalued by (and/or within) Canadian society? And how has this shaped the murdered and missing Indigenous women (MMIW) phenomenon? These have been the core questions I have addressed in this paper. To conclude, I will answer these questions piece-by-piece while providing a short summary of my findings that I have identified throughout this literature review. To answer the how Indigenous women are devalued part, I first acknowledged the importance of the necessity to properly account for Canada’s colonial history. In which Canada was both established and continues to be maintained by white, male European settlers who dominate not only through colonization, but also through patriarchy, racialization, capitalism, and classism. To answer the why are Indigenous women devalued part, it is because of the domination I have just mentioned, which is cognitively embedded within the mentality of white European settlers, because it is they who principally control the political, economic, and ideological spheres of Canadian society. Therefore, due to this inherent socialization of white European settlers, which generally, whether intentional or not (re)produce(s) beliefs of entitlement, racism, sexism, & supremacy; Indigenous women in sharp contrast, are considered far less valuable, & thus far more susceptible to marginalization within the stratas of Canadian society.

To answer how this has shaped the MMIW phenomenon, my conclusion is that it is nothing short of an inevitable by-product of a society structured on oppression, exploitation, domination, & subordination. Moreover, in addition to presenting this social and historical context, I also supplemented my argument and assertions with additional voices and facts in relation to MMIW. In conclusion, I want to acknowledge the, albeit slow, but overall positive progression that this issue has been able to develop over time, since in essence, I have come full circle in this analysis, by beginning first with Canada’s inception, and ending on where it stands today on this issue. There is still no doubt, however, that much more work must be done on this issue, though you cannot deny that these developments are nonetheless progress. Now we can only hope, as well as hold to account, that this new government upholds its promises and follows through on the much needed National Public Inquiry on Murdered & Missing Indigenous Women & Girls in Canada.

References:

-

Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Métis & Inuit (pp. 1-23). (2013). Statistics Canada.

-

Brennan, S. (2011). Violent Victimization of Aboriginal Women in the Canadian Provinces, 2009 (pp. 1-21). Statistics Canada.

-

Cotter, A. (2014). Homicide in Canada, 2013 (pp. 1-33). Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics.

-

Cotter, A., Boyce, J., & Perreault, S. (2014). Police-reported Crime Statistics in Canada, 2013 (pp. 1-39). Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics.

-

Fact Sheet Fact Sheet: Violence Against Aboriginal Women. (n.d.). Retrieved November 24, 2015, from http://www.nwac.ca/policy-areas/violence-prevention-and-safety/sisters-…

-

Fact Sheet: Root Causes of Violence Against Aboriginal Women & the Impact of Colonization. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.nwac.ca/policy-areas/violence-prevention-and-safety/sisters-…

-

Framework for Action to Prevent & Address Violence Against Indigenous women & Girls. (n.d.). Retrieved November 26, 2015, from http://www.afn.ca/en/framework-for-action-to-prevent-and-address-violen…

-

Missing & Murdered Aboriginal Women: A National Operational Overview (pp. 1-22). (2014). Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

-

Perreault, S. (2011). Violent Victimization of Aboriginal People in the Canadian Provinces, 2009 (pp. 1-35). Statistics Canada.

-

Razack, S. H. (2002). Introduction. In Race, Space, and the Law: Unmapping a White Settler Society (pp. 1-20). Toronto, ON: Between the Lines.

-

Sinha, M. (Ed.). (2013). Measuring Violence Against Women: Statistical Trends (pp. 1-120). Statistics Canada.

-

Those Who Take Us Away: Abusive Policing & Failures in Protection of Indigenous Women & Girls in Northern British Columbia, Canada. (2013, February 13). Retrieved November 23, 2015, from https://www.hrw.org/report/2013/02/13/those-who-take-us-away/abusive-po…

-

Truth & Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (pp. 1-20). (2015). Winnipeg, Manitoba: Truth & Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

-

United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (pp. 1-53). (2013). New York: Economic and Social Council, United Nations.

-

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (pp. 1-19). (2008). New York: General Assembly, United Nations.

-

What Their Stories Tell Us: Research Findings from the Sisters In Spirit Initiative (pp. 1-58). (2010). Native Women's Association of Canada.

[1] Missing & Murdered Aboriginal Women: A National Operational Overview(pp. 1-22). (2014). Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

[2] Razack, S. H. (2002). Introduction. In Race, Space, & the Law: Unmapping a White Settler Society (pp. 1). Toronto, ON: Between the Lines.

[3] Razack, S. H. (2002). (pp. 3).

[4] Razack, S. H. (2002). (pp. 1).

[5] Razack, S. H. (2002). (pp. 1-2).

[6] Razack, S. H. (2002). (pp. 2).

[7] Razack, S. H. (2002). (pp. 2).

[8] Cotter, A. (2014). Homicide in Canada, 2013 (pp. 1-33). Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics.

[9] Cotter, A., Boyce, J., & Perreault, S. (2014). Police-reported Crime Statistics in Canada, 2013 (pp. 1-39). Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics.

[10] Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Métis & Inuit (pp. 1-23). (2013). Statistics Canada.

[11] Perreault, S. (2011). Violent Victimization of Aboriginal People in the Canadian Provinces, 2009 (pp. 1-35). Statistics Canada.

[12] Brennan, S. (2011). Violent Victimization of Aboriginal Women in the Canadian Rrovinces, 2009 (pp. 1-21). Statistics Canada.

[13] Sinha, M. (Ed.). (2013). Measuring Violence Against Women: Statistical Trends (pp. 1-120). Statistics Canada.

[14] Missing & Murdered Aboriginal Women: A National Operational Overview(pp. 7-8). (2014). Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

[15] Fact Sheet Fact Sheet: Violence Against Aboriginal Women. (n.d.). Retrieved November 24, 2015, from http://www.nwac.ca/policy-areas/violence-prevention-and-safety/sisters-…

[16] Stolen Sisters: A Human Rights Response to Discrimination & Violence Against Indigenous Women in Canada. (2008). Amnesty International, 26(3 & 4), pp. 105-121.

[17] Kuokkanen, R. (2008). Globalization as Racialized, Sexualized Violence.International Feminist Journal of Politics, 10(2), 216-233.

[18] Fact Sheet: Root Causes of Violence Against Aboriginal Women & the Impact of Colonization. (n.d.). Retrieved on November 23, 2015 from http://www.nwac.ca/policy-areas/violence-prevention-and-safety/sisters-…

[19] What Their Stories Tell Us: Research Findings from the Sisters in Spirit Initiative (pp. 1-58). (2010). Native Women's Association of Canada.

[20] Truth & Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (pp. 1-20). (2015). Winnipeg, Manitoba: Truth & Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

[21] United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (pp. 1-19). (2008). New York: General Assembly, United Nations.

[22] Framework for Action to Prevent & Address Violence Against Indigenous women & Girls. (n.d.). Retrieved November 23, 2015, from http://www.afn.ca/en/framework-for-action-to-prevent-and-address-violen…

[23] Those Who Take Us Away: Abusive Policing & Failures in Protection of Indigenous Women & Girls in Northern British Columbia, Canada. (2013, February 13). Retrieved November 23, 2015, from https://www.hrw.org/report/2013/02/13/those-who-take-us-away/abusive-po…

[24] Find out more about Walking With Our Sisters by visiting: http://walkingwithoursisters.ca/about/