SFU First Nations Student Association Aboriginal Criminology Series

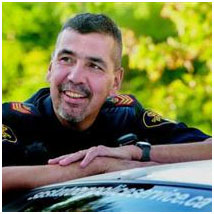

In 1987, Ernie Louttit became only the third Native officer to serve in a city with a significant Aboriginal population. Drawing from his service as a veteran officer, Louttit -- Indian Ernie as he came to be known on the streets --- tells tales of conflict and violence, but most vividly, the realities of marginalized people. Demonstrating a passion for his community, he argues empathy can be the greatest tool in an officer's hands. He is passionate about policing, especially with society's less fortunate, and offers insights into addressing the issues marginalized people face.

This article was originally posted as “'Indian Ernie' leaves the streets” in the Saskatoon Starphoenix on Saturday, September 21st, 2013.

'Indian Ernie' Leaves the Streets

After 27 years with the Saskatoon Police Service, Sgt. Ernie Louttit is retiring and publishing his memoirs. The officer, known on the street as "Indian Ernie," was a key figure in seeing that justice was served in the Neil Stonechild case. In his memoirs he tells stories of his years with the police and the lessons he learned. His perspective is that of an outsider who became a leader within the police service. What follows are excerpts from Indian Ernie: Perspectives on Policing and Leadership (Purich Publishing). Louttit recalls his upbringing in a small Ontario town, shares his observations on the evolution of policing and describes dangerous incidents he faced as a beat cop on the streets of Saskatoon.

My Name is Ernie Louttit

People on the street call me Indian Ernie. I suppose it makes sense. I am a Cree Indian and my name is Ernie.

I have been a police officer for 30 years. Twenty-seven of those years have been with the Saskatoon Police Service.

Like so many native people, I've struggled with my identity. Because I came from an isolated community and was raised without the influence of television and daily papers, I somehow formed my own opinion about what I thought was a Good Indian.

I went out of my way to show I could work, and to show I could take whatever anyone threw my way. Somehow though, I always had the feeling it was not quite good enough. I don't know if it was Canadian society's conditioning of native people, or the native tradition of understating our successes.

Traditionally, most native people disliked or discouraged anyone from being too loud, boisterous, or confrontational. I found over the years that most elders were uncomfortable with me. Too brash and impatient and not willing to embrace traditional teaching, I was never quite sure where my place was.

Even while I was policing, the identity struggle continued. I stayed on the street my whole career because I wanted to be there, mostly for the native community. Because of where I worked, the majority of people I had arrested were native. While policing, I was called an apple, a white man's Indian, and a token Indian. I've even had numerous death threats over the years.

After a while, everybody had a story about Indian Ernie. Sometimes I would arrest someone who did not know me who would tell me stories about Indian Ernie. Ironically, while trying to be treated like everyone else, I had established for better or worse my own identity. Indian Ernie.

Where's Your Bow, Geronimo?

It was in southern Ontario where I had my first conscious encounters with racism. My stepfather had made me aware that I was different from other kids. There were not a lot of native kids in Thorold, Ont. My stepfather regularly referred to me as the little black bastard.

At school I would be taunted with the chants of "Where's your bow, Geronimo?" Kids would regularly do war whoops and dance around in the style of Hollywood Indians. The worst part was that a lot of the kids were older, bigger and stronger than me. They should have known better, but they had to have learned those attitudes somewhere.

All the same, even when I got beat up at school, it didn't come close to the intensity of what was happening in our home. So you just endured.

In an offbeat way, I thank these people for making me who I am today. My stepfather's cruelty and the mean-spirited treatment of the other kids thickened my skin.

From the start of my career, I had to wear three hats. I was a policeman, a native man, and - at first reluctantly - a leader. As a native man, I wanted to be seen as capable and equal to anyone. I never needed a hand up, I just needed no one standing in my way.

When I started policing, the federal government and some segments of Canadian society still had a paternal attitude toward natives, and the police are not immune to it. In the cities, especially in Western Canada, the smouldering issues of racism - on both sides - and the different societies' ability to be tolerant of each other would be tested. I've often said to people that in my opinion, native people want the same things in regard to justice as everyone else. They want to be free of the criminals. They don't want to walk in fear of anyone, including the police.

In my mind, this is where the line got blurry for me. I believe in justice first and forgiveness second. I believe in personal accountability before communal acceptance of responsibility.

Policing has changed so much since the first time I pinned on a badge and strapped on a gun belt. I am starting to feel left behind. Not in a sad or melancholy way, but rather with a sense of pride. I am the new old-school breed of police.

The old-school police who I challenged and fought with through most of my career have long since passed into stories and lessons for those police officers either longing for the good old days or never wanting to repeat them.

My service with the Saskatoon Police Service had its share of confrontations and controversies, but those incidents did not define it. I love the Saskatoon Police Service and marvel at how far it has progressed. I love the young men and women who are its soul and admire the courage and bravery of most of them.

Still, for any of the hard-learned lessons to be effective, they need to be told and retold.

I love the people of Saskatoon. The good people, the bad people, the lost people and even the self-righteous because they taught me every day. Every day I learned a lesson in life, of unbounded generosity and kindness, unspeakable cruelty and depravity, how to cope and how to live.

I've been in the same area of Saskatoon for almost my whole career. It has many names: alphabet city, Harlem of the prairies, and the hood. The population was primarily native, and when I started they were poor and crime-ridden.

The neighbourhood has changed over the years. The crime rate is still high, but there is progress all around. There are new housing projects, new schools and more employment. Progress is starting to choke out the crime.

Throughout my career, there has been a core of people who always, in spite of all the obstacles, moved steadily forward. The people from social agencies, friendship centres, and families who refused to knuckle under. These people shielded the children and protected them from everything they could. When they lost them to street gangs or drugs or crime, the mothers and fathers, grandmothers and grandfathers stood by them while they did the time and accepted them back without judgment or questions.

I would like to be able to say it doesn't matter what race you are, people will see you for who you are. But that is not the way life is.

My being native mattered to a lot of people. It affected the way they treated me. It affected the way they saw me and judged me. No person is ever free of prejudice. How a person manifests their prejudices is the test of their morality.

You Can Always Tell

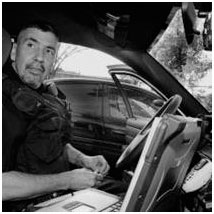

You can always tell how serious a call is by the tone of the dispatcher. You can also hear the 911 calls coming in behind her. Experience fires an extra shot of adrenalin into you as you acknowledge the call and turn your vehicle and your thoughts towards it.

You imagine the worst and hope for the best. If you're the first unit to arrive, you have to take a second to realize what you're seeing so your brain can absorb the shock and formulate a plan.

If you're the second or third unit to arrive, you can tell from the voices of the officers on the radio the seriousness of the tragedy as it unfolds. You hear urgent and clipped transmissions by police officers troubled by what they are seeing, looking for direction and leadership to start to do what they've been trained to do.

When you're the senior officer or the sergeant and you roll up on the call, they look at you relieved and reassured. You get out and take it all in. Preserve life, protect life, and gain control. You ask for whatever assistance is required, restore order, and no matter how serious the situation, except for the technical investigation, in an hour or two it's like it never happened. Traffic is reopened, firefighters have swept up the debris, and the ambulances are gone. The crime scene tape may still be up, but the urgency is gone.

There is nothing left to do except try to process what you have seen and done. And that, my friend, is often the hardest part.

Not everything police do is dramatic or traumatic. There are long quiet nights and uneventful days. It is not always what police do, but rather what we expect police to do. We - and rightfully so - expect police to be ready to respond to whatever calamities life throws our way. We expect a professional and measured response to emergencies. We expect the police will be there.

A police officer does not have the luxury of walking away from a problem. As a police sergeant, one of the things that got my blood boiling was when an officer would throw up his hands and ask, "What do you expect us to do?" As a police officer, you are the leader when you have been called to a situation. Do something! Take action where required, provide alternatives, and provide leadership. Sometimes, just a calm reassurance is enough to resolve an issue.

As a police officer, you have to be aware that everything you do is in the public eye. Everything you do and say is subject to scrutiny. Fair enough, given the authority society has given you.

Everyone has an opinion about the police. Some people can go through their whole life without ever having talked to a police officer, and still they would have an opinion. This is why it is important to teach young police officers the weight of their words and deeds.

Police, like any other professional, must learn their trade. The initial training is only a vessel for experience to fill. As a police officer, you can never stop learning. You owe the community the obligation to learn all you can.

The first love any police officer should have, besides family, is for the community he or she serves. If you do not love your community, all the negative things you see and deal with will cause you to be bitter and cynical. "Us versus Them" is a familiar and sad old story which almost always ends badly.

Saskatoon, Regina, Winnipeg and most major western Canadian cities have high native populations. They also have very high crime rates. Most of the crime is, of course, linked to income. When I first started with the Saskatoon Police, the majority of native people living in the city had the lowest incomes.

Remove the term "native," however, and they were just poor people.

When you're a police officer, it's easy to treat poor people poorly. They do not complain very often. They are stoic in their struggles. They have been conditioned to a hard life. They accept things most people wouldn't and they forgive things most people consider unforgivable.

Here's where the best tool a police officer has on his web belt comes in, and here is where most dangerous things occur if the police officer does not have it.

The tool is empathy. To me, the ability to put yourself in someone else's place is what defines a police officer.

When it comes to finding their empathy tank, there are a lot of things going against someone who has been raised well, is educated and has lived without conflict. Sincerity cannot be faked. It's one of the most transparent of human emotions. Lack it and you lack credibility.

Semper Vigilans

I had less than a year with the Saskatoon Police when I was sent to a domestic involving two senior citizens. The dispatcher said there was no backup available, but I assumed that because of their ages, I would be fine. I pulled up several houses away and walked up to a small wartime house. Yellow with white trim, adorned with old-fashioned curtains and surrounded by a white picket fence with a well-worn gate, it looked like the home of elderly people. The yard was clean and neat. There was a large garden in the back, well laid out and weed free.

I went to the porch and glanced inside. I saw a female at the kitchen table. She appeared to be crying. I knocked quietly and opened the door. The house smelled of liniment and strong coffee. The woman, in her 70s, stopped crying and looked up.

I asked her what was going on, keeping my eye on a closed bedroom door. In a trembling voice, she explained that her husband, who was 88 years old, was being mean to her. I asked where he was, and she pointed to a bedroom door.

I was being complacent, lulled by their ages and the quaintness of their little home. I was going to give the old fellow a good talking to and be cleared of this call for something more exciting.

I went to the bedroom door. It was heavy and solid, covered with many coats of paint and keyed with old-fashioned key lock. I pushed it open gently and saw her husband curled up in bed, apparently asleep. He wore suspenders, a long-sleeved shirt, green work pants and wool socks, even though it was summer.

I turned and went back to the woman to tell her that her husband was asleep and have her expand what her husband was doing to be mean to her. I was not thinking anything criminal had occurred. I got my notebook out and began to write down her particulars when I felt a hard poke in the small of my back.

I heard the distinctive sound of the trigger being pulled on empty chamber. I turned quickly and saw my harmless old man was not harmless at all. He had a rifle in his hand and had fully intended on shooting me. He wasn't a little man either - he was six feet tall and strong. I wrestled the gun from him and tried to handcuff him without hurting him. He must have done manual labour his whole life because it took everything I had to twist him into handcuffs.

The woman was crying again. I was not going to make the same mistake again - I didn't turn my back to her. I called for backup, and another other young constable showed up. I explained what had happened and asked him to call Social Services or see if he could find any family members to take care of the woman. I took the husband to my patrol car and secured him inside. I then checked the rifle. The safety was off and there was a loaded magazine in it. He had not racked a round into the chamber. If he had, I would have been crippled or dead.

It turned out my guy was a retired farmer, married for 50-plus years, and he had the onset of Alzheimer's. He refused to take any medical advice or treatment. He was stubborn and prideful. His family and his wife could not handle him anymore.

I charged him with attempted murder and clearly stated in my report that if he was ordered by the courts to get treatment, I would be satisfied with that remedy.

I got some stupid and sarcastic comments from other police officers as I was booking the old fellow in. Until I told the story - then it was not funny anymore.

Losing is Not an Option

Every police officer who is on the street will eventually be assaulted. Every officer on the street will at some time have to use physical force to effect an arrest. Police officers do their best to avoid this, but sometimes you just cannot.

Losing a physical confrontation is not an option when you are the police. Physical fitness, training and mental preparation should not be an option either. It's your responsibility and duty to be fit and mentally prepared. Your own and someone else's life could depend on it. It sounds dramatic, but it is the truth.

I've been spit at many times, and headbutted, but only once. I have been punched, kicked and bitten. I have punched, kicked and choked out people. I have pepper sprayed arrests and struck them with batons, both the old wooden and new metal ones.

The common denominator in most of these incidents was they happened when you least expected them to. Persons determined to escape or hurt you don't carry a sign saying that's what they're going to do. Instincts and experience will give you some warning, and you need to trust in them.

A person who's going to fight you because you are a police officer does not care who you are. They don't care that you have a family. They don't know or care if you are having a good day or bad day.

Over the years, you learn to play smarter. You try not to go into bars alone, realizing that it is possible to step back and wait until other officers get there. But there were times when you just cannot.

I'm not telling these stories to show how tough I am. Experienced yes, but tough no. I'm telling them to emphasize physical and mental preparedness. If you're a police officer or are thinking of being a police officer, you need to keep in mind that things can happen quickly, and you must be prepared.

Sunday morning, a day shift in April 1997, started off as most Sunday day shifts do, quiet and uneventful. A call came in from a young woman who alleged that she had been held captive and sexually assaulted by her aunt and uncle overnight.

She told us how she had gone over to visit, and after a few beers the couple had tried to initiate sex. When she refused, they overpowered her and sexually assaulted her. Her aunt was an active participant. At one point they used a bingo dabber as a dildo.

We got her medical attention. She was mentally and physically exhausted. After getting a statement, my partner and I went to arrest the suspects. Both of them were intravenous drug users, and I knew them from previous dealings. The male suspect was a violent career criminal with a long string of convictions.

The female who opened the door when we knocked was obviously not expecting the police. As soon as she realized it was the police, she yelled and tried to slam the door in our faces. As there was evidence that could easily have been destroyed, there was no time to get a warrant until the suspects were in custody. We forced our way in. My partner took care of the female and I went in after the male.

He looked wild, high and desperate. He moved to get to a bed, where I later found a large hunting knife. I grabbed his arm and the fight was on. He was high on morphine, so he had a very high tolerance for pain. Control holds were not doing anything, and the arrest just became a fight.

The other constable called for backup, and a sergeant arrived while the male and I were still fighting. I got him into a headlock, and we crashed through a glass coffee table, cutting my wrist. The sergeant took custody of the female, and the other constable came in and struck the male with his baton. It did not faze the suspect at all.

It was not until a third officer came in that we were able to overpower the suspect and force him into handcuffs. Drenched in sweat and defiant, he was pulled, dragged and carried out of the apartment to a waiting patrol car.

I was already feeling the strain of our prolonged struggle, so I knew that when he came down from his high, he would be hurting and stiff.

Once both of the accused were in custody, I cleaned my cut wrist and went to obtain a search warrant for the items described by the victim. All physical evidence the victim said would be there was located and seized. I found the knife the victim told me had been brandished at her to secure her compliance. I found her clothes and the bingo dabber. The bingo dabber still had blood on it. The aunt had had the presence of mind to toss it downstairs onto a pile of laundry while she was fighting with the police.

The male suspect pleaded guilty at his first court appearance and was sentenced to five years in the penitentiary. My cut wrist got infected, and I got blood poisoning.

The female pleaded not guilty and made bail, which she promptly skipped. She was arrested later on the outstanding warrants. She wanted a trial and got it, ultimately being convicted and sentenced to two and a half years in jail. The victim recovered from her ordeal and seems to be doing fine.

I make it a point to tell this story to young constables. Even on a Sunday day shift, you still have to be ready for anything.

There is such a balancing act for police officers when they are on the street. There is sometimes a need to be utterly ruthless, to win the fight with whatever means you have. It cannot be helped - for example, when you tackle someone fleeing from a violent crime. It is violence, fast and furious - tempered, but violence nonetheless.

How do you keep the edge and be prepared for murderous, horrific people and still keep your humanity? All people - or almost all people - have aspirations and want to live peacefully. Some, due to circumstances, cannot, and they end up coming in conflict with the laws of the land. If you accept the premise that most people are good at heart, you as a police officer can navigate this complex and difficult world. But when the time comes, you are still a warrior charged with protection of those who are not.

You have to mix friendly and approachable with just enough attitude to look a little dangerous.

There is an old saying in the Army, "Hard in training, easy in war." It's not exactly true but it is true enough.

The Saskatoon Police Service has improved its training in all aspects of self defence. From shooting to ground fighting, the officers we have been hiring are better trained than I was. Tactically, they operate smarter. But there is no substitute for shared experience, and every story I tell can be looked at several ways: What did we learn? How can we prevent something like that from happening again? Is there a better way? Almost always there will be a better way, and you can always learn something.

Will any police service ever be able to prevent sudden and violent assaults on police officers? No, unfortunately it is part of being a police officer. You accept the inevitable and try to be prepared.

"Do You Know Your Dad's an Indian?"

One summer I took my son to Northern Ontario to visit my family. He was not quite four years old. We were up visiting my father at his trailer on top of a hill. He had converted the trailer into a small summer home. We were outside having coffee when my son whispered to me, "Dad, I need to talk to you." I thought maybe he had to go to the bathroom and was shy because it was an outhouse. He was very insistent, so I went around the corner of the trailer with him.

I asked what the problem was. With all the solemnity and sincerity a child can have, my son looked me in the eye and asked, "Dad, do you know your dad's an Indian?"

A Warrior Who Sleeps Outside the Camp

I have never been a traditional Indian. My analogy is, I am like a warrior who sleeps outside of the camp: No one really wants to see or hear from you until you are needed.

I know a lot of people draw strength from tradition, and it is important to maintain some traditions. At the same time, we need to create new traditions and adapt to change. There will always be some people in any group who get left behind, and that cannot be helped. We all need to push forward for the future generations.

I like to think that I have pushed forward, although I was always reluctant to think that I could be seen as a role model. All of us have our own faults and character flaws.

I have always tried to be as honest as I could about how I felt. Age and maturity help to embolden the way we talk as our beliefs and convictions are entrenched with time. The way I dealt with racists and prejudice was by example. I would work and let the results from my work speak for me. I would outlast people who put obstacles in front of me.

I am a native and am proud of being a police officer. Sometimes I wish I was seen as a police officer who just happens to be native. But as I said, sometimes my being native was very important to some people.

I'm getting close to retirement. When people ask me what I hope to accomplish before I retire, I tell them I want to train my replacements. I want people I have met to have a different view of police and who we are. I hope I can inspire police officers to be dedicated and empathetic, police officers who are in all respects better at what they do than I was.

I hope I can inspire some native kids to see policing as a true and honourable profession they want to be part of. It took me years to learn how to deal with people, but I believe the insight people gave me is transferable. If I can give anyone insight without the sting of hard-learned lessons, I will.

There's always reluctance in some people to see themselves as leaders. I was like that for years, and now when I see someone who has leadership qualities I tell them not to be reluctant to do what comes naturally. Empathy, leadership, and commitment are qualities I have always admired. So if you possess these qualities, I want you to have my job.