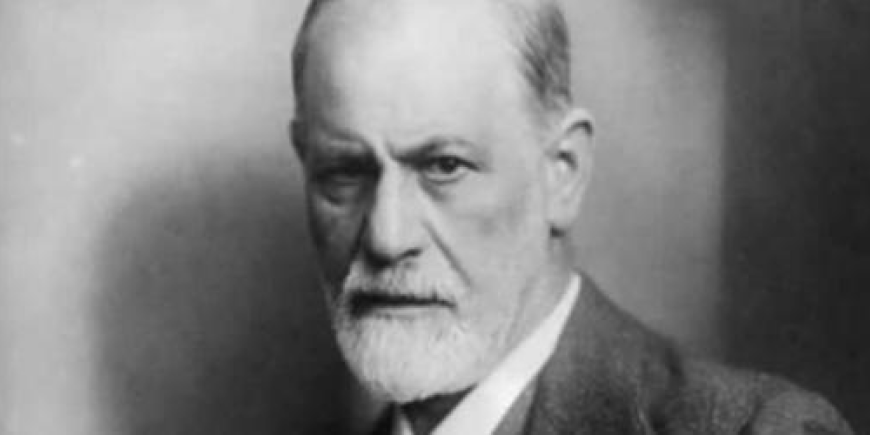

Of all the posts I’ve written, the one that seems to consistently get the most page views is this one on strengths and weaknesses, Freud, and Alfred Adler. I guess there’s a lot of psychology students out there scouring the web in search of information on how these two prominent historical figures viewed the issue. If that’s the case, then I feel a little bit bad for them, because whatever knowledge I have about these two theorists likely derives from the same sort of textbooks that their courses are using in the first place. Although I suppose my writing is probably a bit more entertaining than that of most psychology textbooks (faint, faint praise).

Among psychology buffs, Freud can be a very polarizing figure. There are some – including close friends of mine – who strongly contend that he (and by extension classical psychoanalysis) single-handedly set back the progress of psychotherapy by decades, permanently etching a black mark on the history of psychology thanks to theories that seem almost non-sensical when viewed through a modern lens. What can I say? I guess people get a little sensitive when you tell them they unconsciously want to kill their father and sleep with their mother.

Unless they’ve blocked it out, anyone who’s majored in psychology during post-secondary studies should have a pretty good idea of Freud’s basic theories, as most psychology classes seem to cover them in the first week or so. Honestly, if you asked me what two things I was taught most frequently in my undergraduate psych degree, Freud would be one and “correlation does not imply causation” would be the other. In my experience, the latter was taken very seriously by most professors, while the former seemed like a halfhearted chore (perhaps the reverse is true in classes on literary theory?). In consequence, most psych students probably write off Freud as crazier than the wealthy female patients he so loved to treat.

When it comes to psychotherapy, classical Freudian psychoanalysis seems to have little to no resemblance to what’s generally held to be good practice these days. Things like empathy and building a therapeutic relationship based on trust, genuineness, and caring just don’t seem like priorities when you’re laying on a chaise, facing away from your silently note-taking therapist, saying whatever comes to mind for hours, weeks, months, years. Thankfully, while contemporary psychoanalysis has much in common on a theoretical basis with its’ classical cousin, in practice it shares more with more modern, humanistically-informed approaches.

Freud did have some crazy ideas that I have a hard time making sense of today, and I would indeed be hard-pressed to apply them to a therapeutic context in order to effect change in a struggling client. Nonetheless, I find the man to be a simply fascinating historical figure. The same friends who swear that the discipline of psychology would have been better off without Freud have probably labeled me as a “Freud apologist” as a result. I’m not quite sure what I’m apologizing for, but the term seems to make sense as I have been known to play the part of Devil’s Advocate in heated theoretical discussions in the past.

One of the things I talk about in my current work with students in a career development role is risk-taking. No, not the kind of risk-taking that convinces you to jump off a hundred foot cliff on a last-minute camping trip to Jasper, nor the kind that involves losing large sums of money in places where you can drink openly in public streets. I’m talking about career-related risks. Embracing uncertainty and open-mindedness, and taking a step in a new direction. Taking meaningful action towards an inspired direction without worrying too much about the consequences. Ignoring the voice in your head that convinces you to stay at the job you hate or to take classes you can’t stand because your parents want you to go to med school.

I think I respect Freud as much because of the risks he took professionally as anything else. Here was a man who, in the late 1800s, in the middle of a successful medical career, started to have some ideas that were way out of synch with professional and societal norms. This was the time of “fallen women” in literature, and a time when even mentioning the word “sex” was a severe social faux-pas – especially in the elite class of society that Freud was a part of. So what does Freud decide to do? He writes a book that is essentially all about sex. He outlines an entire theory of human development using sexual terms. He basically states that all human behaviour is sexually motivated. Yes, his patients were mostly upper-class and female, but he also started to expose, for the first time, the abuse that these women were experiencing.

Talk about a career risk.

Ultimately Freud’s risky ideas, and the rigidity with which he upheld them, cost him many friendships – among them Carl Jung and Alfred Adler, two other big-thinkers of the era in depth psychology. He was probably a really hard guy to get along with – maybe a real jerk, even. But that just makes him more interesting. Hence my continuing fascination with Sigmund Freud.