I was chatting with an old friend not long ago about his career. His is an interesting story: currently a part-time farrier (one who shoes horses) with a full-time triathlon training schedule (competing at the world triathlon grand finals next week in London - go Richard!), his career trajectory originated in the culinary world. After completing his studies, he worked in a small restaurant for several years, and was pretty much running a whole kitchen by the age of 19. I don't know if readers will appreciate how remarkable that is, but suffice to say I saw very little of him during this time due to the crazy workload and number of hours required.

Eventually, he decided to switch gears - maybe it was burnout, maybe it was just an itch to try something different - and become a farrier. He did an apprenticeship, found a great job, and eventually struck out on his own in the horseshoeing business (and did very well, I might add). Everything looked great - he enjoyed the work (his family has a history of breeding racehorses, so he always had an affinity for the animals), he liked the people he was working with, and he was making great money.

That is, of course, until the day that he was trampled by a horse (I'm told this is actually a pretty common occupational hazard). Thankfully, he wasn't killed, or even crippled. He was lucky enough to only walk away with a back injury that took him a couple of months to recover from. Needless to say, it was a wake-up call. What if it had been worse? What if his body - which in addition to the injury had already begun to show the physical toll of the profession - gave out on him? Should he continue with shoeing horses, or go back into cooking, which he always felt was his passion?

All that to say he was dealing with some career uncertainty at the time of our conversation. We talked about a bunch of things, but one thing I said seemed to resonate with him:

"The best career is the one that allows you to be of most service to the world."

It got him thinking about his situation in a different way, on a bit of a higher level. That's not to say he made any major decisions as a result, but it seemed to give him a renewed perspective on his decision making. It's something I strongly believe.

I recently came across an interesting argument. It went something like this:

"It's immoral to study something that is not in demand according to labour market needs and projections."

The sentiment was expressed in a book recommended to me by a client recently, which I haven't read but got a pretty good idea of from the summary and reviews (I probably wouldn't recommend the book myself, but here's the link). The strange novelty of this idea, amid said book's slough of shortsighted, ill-researched, and ideologically contaminated theses, was notable enough to get me thinking: is there something there?

The idea certainly makes sense on a surface level, as long as we think of morality from a systemic perspective, but a few fundamental assumptions would have to hold true. If we can assume that labour market projections are reliable and accurate, and if we can assume that morality can be mostly described by what's good for the economy, then I can see the argument holding water. The question of interest here essentially becomes: what net benefit are you offering to society? If the answer is 'slim to none,' then it might be fair to say that the decisions that put you in that situation were immoral ones.

There's a different way of looking at morality from a large scale perspective: it's a word that Adlerian psychotherapists love: Gemeinschaftsgefühl.

Gemein-what now?

Gemeinschaftsgefühl is a German word roughly translating to social interest. In Adlerian theory, one's psychological health is thought to be directly related to how socially interested one is. Put another way, if we feel disconnected from our community (family, friends, coworkers, peers, various concrete and abstract groups, even humankind as a whole), then we would rightly expect that it would only be a matter of time until we started to become dysfunctional.

Another facet of social interest lies in how much one is able to contribute to the larger community and world around them. This sounds familiar to our idea about morality above, only with much more nuance.

Can I be socially interested if I study a subject that is not currently in labour market demand?

I think the answer is an unequivocal yes, and I've got two reasons you should think that way, too.

Predicting the Labour Market is About as Reliable as Predicting the Weather

And neither is very accurate beyond a short-term forecast. There are simply too many factors to consider, too many variables whose interactions are impossible to measure aside from observing large-scale patterns. These are chaotic systems with very little long-range predictive value. Small changes in any one area of the system can potentially lead to massive changes in another part of that system (i.e. the butterfly effect). Completing a university degree usually takes a minimum of 4 years - that's a lot of time for things to change, particularly in the fast-moving, technological knowledge-based economy we live and work in. Being that labour market projections tend to come in 10-year intervals, there's a big old grain of salt to take before making big life decisions on that basis.

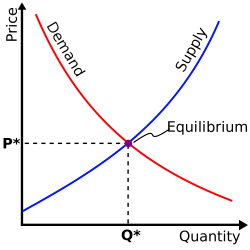

Good for the Economy Does Not Necessarily Equal Good, Period

I think the easiest fault to find in the "low demand = immoral" argument is that morality on a social level encompasses so much more than economic benefit. A social worker with a non-profit organization working with low-income communities doesn't exactly make a big economic impact, but the amount of "good" they are capable of doing is - while impossible to quantify - immense. A talented artist struggling to make ends meet doesn't make their difference to society financially, but culturally through their creative works. To suggest these people are immoral to pursue careers that aren't "in demand" while ignoring the contributions they make to society is nothing short of ridiculous.

When it comes to morality and the labour market, I think we could all benefit from a little less supply and demand, and a little more gemeinschaftsgefühl.

Just sayin'.